| 19. The Aftermath. |

Liberated! – What a lovely, sweet-sounding word it was…and what a glorious reality. The Occupation had lasted four years, ten months and seven days.

The celebrations amongst the civilian population went on for days, from house to house, in the streets and parks…almost any place where people could gather, no longer bound by the oppressor’s rules against congregating (outside of church). For the administration, however, it was a matter of getting the Islands back into full operational mode as quickly as possible.

Banks and businesses would need to be opened, with supplies of every imaginable sort needing to be brought in. Rules and regulations instituted by the Island authorities during emergency would need to be rescinded so normal law and order could be restored. The States (or as many members as were present at that time in the Island) met in extended session with representatives and advisers of the British Government (who had been hurriedly flown in to assist) to attend to the essentials of restoring civilian rule. The British Government had already prepared financial and practical aid programs, the implementation of which required the creation of countless departments and committees to oversee their operation. These and numerous other “instruments of bureaucracy”, for which the British government of the day were well renowned, were rushed into place with amazing speed and efficiency to enable the population to get their lives back in order with the minimum of fuss.

There was, it seems, a certain amount of political expediency in this flush of activity, as it was clearly perceived by the observers from England that many Islanders considered that their Isles had been abandoned and then forgotten by Britain for the duration of the occupation.

(There were, obviously, far too many implications to the dilemmas facing the British Government during the conflict, in respect to the Islands, to delve into in this book. Suffice to say, they posed a situation without parallel in the Empire’s history.

The Islands and the people’s welfare had been raised regularly in parliament over the past five years, especially by Winston Churchill and Lord Portsea but, in view of the ‘bigger picture’, they presented a true conundrum. In hindsight, things could have been done better on their part…but isn’t that always the way?)

Three factors in particular did seem to raise their heads though:

1. Why didn’t the government use the services of the BBC to send messages to the population?

2. Why were Red Cross parcels not sent earlier instead of arriving so late in the piece?

3. Why had they not sent medical and other essential supplies?

In brief, the answers were:

1. The degree to which the Germans would be monitoring the airwaves was uncertain. The British authorities did not want to put the islanders in further danger by having the enemy purport that intelligence information was being sent to an underground resistance movement, resulting in possible reprisals.

2. The Channel Islands population did not fit the classic P.O.W. criteria, as allowed for in the Geneva Convention. It was also feared that the enemy would confiscate the food supplies to supplement their own. Further, it was also a fact that aerial surveillance observations indicated that the crops and stock of the Islands were faring very well therefore food must be in good supply.

3. Vitamin D for children, insulin for diabetics and other medical essentials were sent in limited supply along with the Red Cross parcels but, once again, there was a fear of the enemy purloining anything more for themselves.

One of the first services to be restored was the Post Office, in conjunction with the Red Cross and how busy they were from the first day of restored business. Both Gilbert and Irene thought to get off quick letters to their parents, informing them of their current situation and state of health.

A pastor’s job in the rapidly changing social environment of the aftermath of a trauma such as the Guernsey people had survived was without precedent in the life of a denomination as comparatively young as the Elim Church. What sort of training could have been provided to prepare and enable a minister-in-training to face such an unthought-of situation as this?

The whole of the occupation was difficult enough in itself…albeit with the blessed ‘up-side’ of the sense of inter-dependency and unity generated amongst the population thus creating an ideal environment for ministers and their ministry…but on the other hand, liberation proved to be the antithesis of that expressed need. Now, here was Gilbert – one lone Elim minister for three good-sized churches – in a social environment becoming embittered at what was being heard and found out, as many rumours and truths of the past five years unfolded. Doubtless the ‘traditional’ churches (C of E, R.C., Methodist, etc), which had survived through centuries of wars, were able to impart some measure of expectation of what had become to them part of their culture of ministry but to a young revivalist denomination this was all new.

Despite the outward elation of liberation and without the unifying factor of a common enemy the community retreated to their own hurts and fears as accusations about collaborators, fraternisers, privateers and even traitors surfaced. Young ladies who had been only too willing to grant ‘favours’ to the German troops became particular targets of anger, labelled “Jerry-bags” (sometimes even having their heads shaved) and ostracised. Those Islanders who had evacuated also came in for criticism, as news flooded in from the mainland of how well they had been received and cared for, living very well in comparison to those who had stayed behind. The terms “cowards” and “runaways” were heard in conversation. This issue became even more sensitive when returned evacuees, upon being told “You turned and ran like rabbits,” retorted with, “Yes, we went off to help win the war whilst you were here, all cozy with the enemy!”

The post-occupation problem seemed, at its depth, to stem form fear of the unknown of the brave new world outside to which they would have to adapt…a world that had, by and large, moved on without them as they had remained in a little ‘time-warp’ not of their own making. The once-confident and self-sufficient society of well-to-do farmers, entrepreneurial holiday hosts and business bankers now felt like the poor country-cousins. Adaptation was not going to be easy and to be told so, under pressure from Westminster, did not make the pill any easier to swallow despite the massive injection of millions of pounds England was prepared to pour into the Islands to return them to viability.

[The Germans had forced the Islands’ Administrations to borrow heavily from British and foreign banks to pay for the occupation, to the tune of ten million pounds. As a post-war expression of sympathy for the Islanders – on the part of the British government, who exerted pressure on the banks – these debts were reduced and in some cases forgiven. As their contribution, Britain granted a total of seven and half million pounds, partly to liquidate ‘unforgiven’ portions of the loans, the remainder to restart the local economy.]

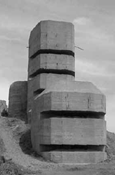

On the surface, the clean-up began. Of the 30,000-strong garrison, 27,000 were transported off to P.O.W. camps in Britain. 3,000 were required to stay behind and work with the British forces to identify and remove mine-fields (land and sea), decommission armaments, reconstruct damaged buildings, repair property, assist with road restoration (caused in part by movement of heavy military machinery) and generally help clean up. Services slowly returned as power and water were once again turned on.

With the return of electric power, evening worship services and gatherings could resume on both Sundays and weeknights. Routine and normality began to return to church life and Gilbert was now busier than ever, still with three churches to oversee.

The need for personal visitation, prayer and counselling increased daily to a point where his resources were stretched to the absolute limit. Numbers in attendance had begun to drop off and much time was expended following up on the spiritual needs of those who were missing. Sadly it appeared that amongst the congregation that the high degree of dependency upon God, desire for close fellowship and hunger for prayer generated in the difficult occupation days had slackened with freedom’s arrival…but the shepherd felt compelled to ensure not one member of the flock was abandoned.

In the broad daylight of hindsight, every aspect of life was questioned, even the role of the church. Most of the flock stood firm but some, who had come in from other denominations, raised a few problems.

[In the general environment of suspicion there was even a hint of question about Gilbert’s fellowship and association with Herman Lauster but nothing ever came of it…and neither should it have.]

At this point in time, Gilbert needed two things…firstly, some replacement pastors to take over after the Vazon and Delancey churches; secondly, a break back home in England. On June 13th, he wrote to Rev W.G. Hathaway, making his requests known to the Elim HQ.

June 7th, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth made an official Royal Visit to Guernsey. [They had been scheduled to visit the previous day but were unable to do so due to bad weather, which prevented their aircraft from operating.]

During an open-air meeting, in reply to the Loyal Address from the Bailiff, the King said that he had been deeply concerned for his people in Guernsey and Sark all through the years of the German occupation but that he was greatly joyed that the Channel Isles, the oldest possession of the British crown, were once again enjoying freedom. The listening population were elated by their presence and the words of encouragement from their Monarch who, alongside his Queen, had walked amongst the bombed-out ruins of London during the Blitz. The empathy he felt with his people was clearly registered and they cheered him everywhere he went in the Island that day. Naturally, the crowds were delighted to have their King and Queen amongst them.

The news was not quite so good for Gilbert, though. The owners of the house in which they had been living were due to return to the Island, meaning that Irene, Michael and he would have to return to the apartment upstairs in the church.

The situation with relief pastors was not so good either. Elim HQ replied that they were in dire straits themselves, being short of men to serve all the churches in the mainland…particularly single men, who would have been more suitable for short-term relief. Most of the pre-war single pastors had married during the war years and due to the national call-up, there had been few new students enrolled. They would, however, like to have sent Rev Techner to relieve Gilbert for a holiday but were faced with the problem of obtaining a permit for him to travel to Guernsey.

With the situation in the Island as it now was, the authorities had found it necessary to restrict new entries to Guernsey, there being so many British troops and government advisers there – in addition to the numbers of evacuees wanting to return. Permits were being issued under very strict guidelines and qualification was most difficult. Despite the Anglican, Catholic, Methodist and even Salvation Army being allowed to have either visits or relief from members of their British headquarters, Elim could not obtain the necessary permission.

By the beginning of August, the family were resettled in cramped conditions in the little church flat once again, an active youngster making the location anything-but-ideal but, with perseverance and patience, they pressed on with their ministry in the hope of a break before Christmas.

Regardless of the heavy workload, Gilbert found time to write an article for the “Elim Evangel” which appeared in the September edition.

Correspondence between Gilbert and Elim HQ indicates that both ends became actively involved in harrying the powers-that-be for the necessary travel permits – both in and out – for Gilbert and the family, as well as Rev Techner…with Gilbert even expressing the hope that they would be in the mainland in time to join in a great celebration rally in London on September 1st, despite being able to obtain a travel permit [for travel as early as July 12th!] for themselves for their planned departure at the end of August, Rev Techner’s permit was still not granted.

Finally, however, with the paperwork ultimately settled, the exchange was transacted and the weary travellers arrived at Weymouth.

They stayed a few days in London at “Woodlands”, Elim Bible College in Clapham to enable them to join in special services of thanksgiving at the Clapham and Kensington churches. They were also able to visit Irene’s family in London, before making their way to the seaside. In the peace and quiet of Hove they could unwind at the home of Gilbert’s parents.

Needless to say, both families were shocked to see how thin and pale they were, although amazed at their general good health. Michael recalls that Irene felt almost ashamed at his physical condition and remembers seeing the stunned reaction from people whom they met and frequently hearing the comment “He looks like a Belsen child” [a reference to the much-displayed photographs of emaciated children liberated from the infamous Belsen concentration camp.]

With much sleep, quiet rest and good food however, their bodies were fortified, whilst fellowship with church, family and friends lifted their spirits. Gilbert visited some of his colleagues from the early days of his ministry whilst Irene and Michael spent time with both sets of his doting grandparents, enjoying the rest and care. How they needed that break.

Returning to London, Gilbert spent time at Elim HQ, presenting a full report of the work in Guernsey during the past five years as well as catching up on changes and progress of the work on a national level.

A summation of the effectiveness of the work of Elim in the Island during the occupation was reflected in an article by Guernsey historian, Herbert Winterflood, in the Guernsey Press in January, 2003 in his series “Christianity under the Jackboot”, where he concluded his final episode with the closing statement… ‘It is obvious that the Elim Churches contributed a great deal of spiritual life to the island in those difficult days’… And so they had.

……………………………….

EPILOGUE: The latter years.

1952 saw the emigration of Gilbert and Irene’s family (now four in number) to New Zealand, to establish the Elim Churches.

Then, in 1965 after 13 years of pioneering work, Gilbert and Irene were invited to the UK for a preaching tour of Elim Churches, which provided them with an opportunity to revisit Guernsey.

As they were preparing their itinerary, news reached them of the death of Herman Lauster, with whom they had lost contact after moving to New Zealand.

His biography was being prepared by the Lauster family and an invitation was extended to Gilbert and Irene to visit their home in Germany, en route to England, to have some input in its writing.

Delighted to be able to contribute memories of their friend and as well as some insights into conditions of living during Herman’s time in Guernsey, they agreed to do a recorded interview as a resource for the writers. The welcome they received from the Lauster family, in the Black Forrest, was one of genuine warmth and sincerity.

It was here they learned more of what had happened:

- When the end of the Occupation came, with the arrival of the British navy and troops, it happened for Herman just as he had seen in the vision.

- Within days he was shipped off to Prisoner of War Camp 23, near the market town of Devizes in Wiltshire, England.

- During his year of incarceration, he wasted no time in evangelizing the hundreds of disillusioned soldiers in the camp and it would be accurate to say that a revival broke out amongst the prisoners as he preached to, and prayed for, these spiritually broken and wounded men. [Some of the Nazis in the POW camp even made an attempt to take Herman’s life.]

Gilbert, once becoming aware of Herman’s whereabouts after he was taken prisoner, had actively tried to initiate efforts to have him released, through the government resources available to him in Guernsey.

- At the same time as Gilbert had been trying to lobby for Herman’s release, the American branch of the Church of God pursued the same goal, utilising connections with the US Forces through their chaplains. Church leaders in Germany made similar appeals and on August 2nd, 1946 Herman was finally released.

- After the end of the war, he returned to Germany to continue a successful, albeit strongly resisted, ministry which led to the establishment of many Churches of God assemblies across both Germany and neighbouring France and Switzerland. Helplessness and despair, for many, was turned to joy and hope wherever Herman preached.

- Ultimately, he became the prime catalyst for the expansion of the work of the Church of God in Europe.

- On Tuesday September 9th, 1964, whilst preaching at a convention (held, ironically, in Adolf Hitler’s former summer retreat town of Berchtesgaden), Herman passed away in the pulpit.

To this day, the Church of God holds Herman Lauster in high esteem as one of their ‘Missionary Heroes’ for his ministry in South America as well as Germany.

Herman had played a significant role in Gilbert and Irene’s lives during those dark days and they were delighted to have been able to contribute their memories of this fine servant of God.

Although Gilbert and Irene would spend the greatest part of their lives in New Zealand, Guernsey would always hold the dearest place in their hearts to the end. Whilst friendships made in New Zealand were indeed dear, somehow the Dunks felt ‘unrelated’ in the same sense as they did to the ‘Guernsey family’.

It has been said, ‘the truest friendships in life are forged in the fire of common adversity’ and so it was for Gilbert and Irene…and their boys…both of whom considered themselves as ‘born & bred Sarnians’ (Guernsey-men).

Gilbert and Irene have passed to their Heavenly reward, now. The legacy they left will only be known in eternity but in every endeavour of his life, his work can best be summed up as “Occupation: Pastor!”